You don’t realize how powerful a grizzly is until you see one in person, mere yards away from your kayak, while they deftly slice open salmon and roar at each other. Holyyy shit. I clapped eyes on more than 20 grizzlies over the course of four days on a remote alpine lake in Western British Columbia, and I loved it.

You know the noises that the dinosaurs make in Jurassic Park? Pretty sure those are bear recordings. (Edit: I was close! Koala bears are the T-Rex!) It sounded like dinosaurs were bellowing throughout the woods surrounding our tents each night. Fear didn’t hit till I needed to pee at 3am. The bathrooms are a very short walk away from the safety of our elevated tent platforms. 3am in the remote wilderness is truly, completely dark. A short walk was actually a long, slow, grappling-through-the-dark endeavor which I thoroughly underestimated. I could not see my hand in front of my face. Our guides taught us that the bears aren’t inherently dangerous; just don’t sneak up on them, scare them, mess with their cubs, or leave food out. To avoid sneaking up on them in the dark, as they were audibly nearby, this was my bear talk:

“Dont be scared bears! I’m coming to pee!”

Yeah the whole campsite loved that.

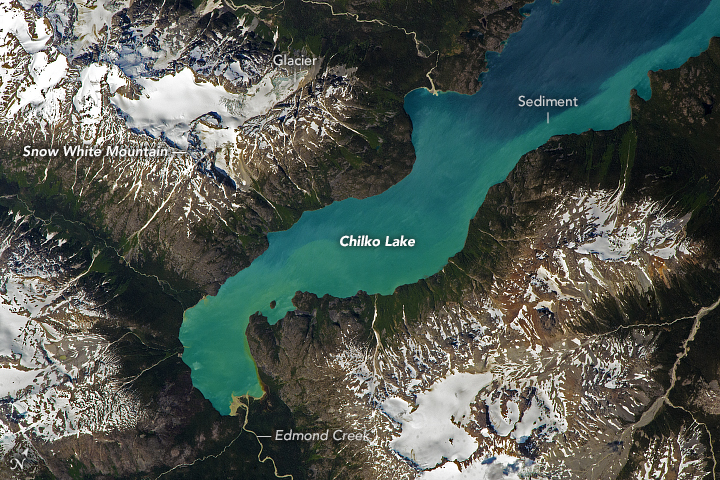

I arrived at Bear Camp on September 17, 2016 via an itty bitty sea plane with strict weight restrictions. The view was stupendous, all glass blue water snaking between fluffy clouds. We landed at Chilko Lake, locked away all food and petroleum products (PRO TIP: Bears love chapstick), and hit the ground running with a 21 mile inflatable kayak journey downriver. This is the most active trip I’ve ever taken, but also the most relaxing. Many broken rythms of daily city life were corrected overnight. I was hungry when I was supposed to be hungry. I was tired by nightfall. I slept well. I had energy all day. We stuffed ourselves with homemade meals and woke up to a fresh cup of tea or coffee outside our tent at dawn. One of my favorite memories is poking my head out of the warm safari-style tent into the frosty dawn air just to grab my hot coffee, then quick back into bed for just a few extra moments of lazing around. We drank in the views of the glacier-carved alpine lakes. We rode horses, climbed mountains, biked trails, and explored the world around us during every daylight hour we could.

Kayaking became my daily ritual. I most enjoy nature when I can experience it alone, and our camp afforded us the independence to do so. We were free to grab a kayak and go out at any time, provided we didn’t go in to dangerous waters or too far from help. In the morning when the light was weak and there was still fog on the lake I slipped my kayak into the water and paddled along the shore. I drifted past distant grizzlies and black bears, eagles and loons, feeling like a national geographic explorer.

The mornings were never quiet. A euphony of wildlife noise echoed over the water all the time. But it wasn’t intrusive, loud noise. It was the soothing trills of loons, shuffling of bears, and cries of adolescent eagles whose heads had not yet whitened. The harbinger of all this wildlife is the salmon. More than 1 million sockeye salmon bring hordes of grizzles and eagles to feast every fall. One bear, Xena, was more blonde than the rest and a fairly common sight. Another, Gimpy, was smaller with a slight limp.

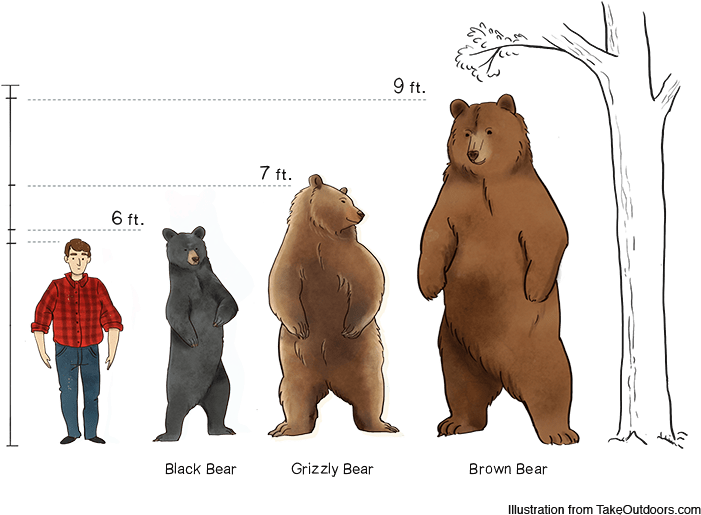

At one point myself and 3 kayakers were enjoying a paddle downriver and took a narrow left fork around a median of land in the center of the river. What we did not know was that this narrow passage was later flanked by Xena and Gimpy on opposite sides. Xena was on the bank to our left, face bloody with salmon. Gimpy was on the median to our right. To our dismay, they were keenly aware of each other. Xena waded far out into the water to roar at Gimpy, but Gimpy wasn’t going anywhere. He grunted, tossed his head at her, and entered the water from his side. For every step they took towards eachother, we drifted a yard closer. In seconds, we held our breath and floated between between two angry Grizzlies. I remember white-knuckling my paddle. I stared at Xena, not 20 feet away from the nose of my kayak. I could see the droplets of water clinging to her individual hairs. She did not even glance my way. The bears could have lunged and locked jaws at any moment, but for the plentiful salmon that made a territorial spat pointless. Xena went back to her fish, still so close that I could hear the flesh ripping as we rounded the bend. Let’s all keep in mind that a brown bear can run 10 feet per second, faster if they weigh less, with top speeds outpacing Usain Bolt. Easily the scariest, but most exhilirating, animal encounter of my life.

Gizzly Bears vs. Brown Bears vs. Kodiak Bears

Let’s get into the nerdy factoids I learned during my trip 😀

The brown bear is the parent species. Grizzlies and Kodiak bears are sub-species of brown bears. Grizzlies have a more “grizzled” appearance with light-tipped fur, live more inland than in coastal areas, and are arguably more reactive and aggressive. Kodiaks bears are specifically brown bears that have lived in genetic isolation for centuries on Southwest Alaska’s Kodiak, Afognak and Shuyak islands. They are the world’s largest brown bears (1,500 lbs!). So if you’re up in the mountains, prairie, or tundra, and you see a brown bear, it’s a grizzly. If you’re down on the coast, it’s a brown bear.

Then there’s black bears, which can have brown fur. You’re welcome.

First Nations People

First Nation People are to Canada what Native Americans are to the States. We clearly visited during a time of unprecedented land transfer from the Canadian Government to the First Nations people. A 2014 Supreme Court of Canada decision granted Chief Roger William, on behalf of the Xeni Gwet’in people of the greater Chilcotin Nation, 1,750 square kilometres of Crown land in the Chilcotin area. Chilcotin aptly means “people of the river”. No clear legal stance seemed to exist for the few homes and business (like Bear Camp) already operating on tiny pockets of “private” land in the area now given to the Chilcotin Nation. We visited some homesteads deeply nestled in the mountains, not accessible at all during wintry months, which had substisted there for hundreds of years. Yet even prior to those families were the First Nations. The families there still work the land and live snowed-in through winter on the fruits of their labor. We broke bread and drank beer with both ranchers and First Nations people during our stay. We were also stopped, questioned, and redirected by First Nations people while trying to kayak the river. I did not have the background nor opportunity to delve into this topic then, but I wonder how their relationships have evolved and how they continue to operate now.

Passport Potatoes Trip Rating:

Overall 10/10 Potatoes. I’d go again!

We’re working on how we rate our trips…maybe something like this?

Food: 8/10

Comfort: 6/10

Culture: 7/10

Animal Encounters: 10/10!!!